All but two of the windmills on the ranch were built to the same design, but no two were alike when the wind put them to work. Visible for miles jutting above the chaparral, each sounded out a tuneless melody, an almost unbroken clanging, slow and comforting and rhythmic, coupled to the occasional metal-on-metal squeal of the tail adjusting to a shift in the breeze, its blades slicing air with a tempered whoosh, pulling up clear cool water flowing steadily into the cistern through the long galvanized discharge pipe. It was as though these lone sentinels scattered in a sea of brush breathed a personality all their own. There were ten in all, staked across 11,500 acres, and the taste of their waters was as distinctive as their lonesome resound.

To the north, the Salas windmill at the upper reaches of the property produced water with a slightly salty flavor. Only the dogs, cats, and cattle tolerated it. Though, to hear Mom tell it, Dad preferred it for brewing his morning coffee. The water was of such poor quality that Dad’s effort to establish St.Augustine in the yard when we first moved there failed. Weeds, grass burrs, and buffel grass thrived, however.

A mile and two-thirds to the southwest, Las Lagunas windmill offered a neutral-tasting water, good for icing down in a galvanized five-gallon cooler to quench thirsty men up to their elbows in ranch work. Although, my kid brother Ricky detected a slight greasy taste at times. There really was nothing to discourage its drinking if it were allowed to air for a while. Las Lagunas was the pasture where Poncho Cantu rode his last, dying in the saddle, still working his trade at age seventy-five. The cowboy’s heart gave out.

One and two-fifths miles west southwest of there, El Coyote’s windmill pumped to the surface a water rich in mineral taste, but not so much that it failed to satisfy your thirst on a dry, dusty, blistering hot summer afternoon working cattle. Kid brother Danny remembers a slight saltiness. The corrals at El Coyote were where we once happened on a fresh poachers’ kill. Driving into the large holding pen one winter morning, a young buck and two does were discovered lying dead on the ground, scattered in the fenced clearing, still bleeding out and warm to the touch. All we found were boot prints in the sand leading away and no trace of the poachers, but we could feel their eyes studying us from the brush line beyond the bull wire. The unwelcome intruders had more than a two-mile empty-handed walk to the highway to make good their escape. Of course, we took their kills.

A mile southeast of the crime scene stood the Doghouse windmill, bringing up the sweetest-tasting water of all, so soft it was difficult to lather up soap. Next to the Salas well that reached 300 feet into the ground, the Doghouse windmill was the second deepest of the ranch. That windmill produced all the water I ever drank in my formidable years up to age thirteen. The water left your hair with a clean squeak after a bath and a baby-smooth feel to the skin.

One and a third miles west stood the Four-Fifty windmill. Dad and his nephew, Juan Ruben, built that windmill from two-inch pipe in the early 1960s. I never saw so many spent welding rods littering the ground where the project was realized. Dad used an old metal wagon rim with spokes for the service platform that was high above. When the windmill first drew water to the surface, Dad held out a cupped hand after it had pumped a while and took a cautious gulp. At first, he declared it sweet, but after subsequent tastes he reassessed, declaring it had a tinge of rotten egg. Drawing water up for several days, the odd tang later dissipated, and it took on a neutral quality.

A mile to the northwest was Las Pamoranas windmill. It offered drinkable water with little to distinguish it. Some of the older pens in its corral were noticeably tall. Dad said they were built that way years before to keep steers from clearing them with a jump. It is surprising how far off the ground an eight-hundred pound animal can leap into the air when it has had enough of the crowded fuss in the corral.

Six-tenths of a mile to the northwest, across Highway 359, the Westside windmill delivered water not unlike Las Pamoranas. Once, when Dick Shimmer and I were servicing that windmill, I discovered more than a handful of nuts and bolts missing from key areas up high near the platform. It was a wonder the whole operation had not fallen in on itself before then with all the rattling and shimmying.

Cutting back southeast across four and six-tenth miles of brush, the Herberger windmill poked its ten-foot fan over an old mott of mesquites that encircled an earthen tank. That well offered mineral-laden water, drinkable, but nowhere delicious like the Doghouse windmill’s. Those were the pens where Dad was seriously injured by a crippling kick to the spine from a steer. That cost him several weeks in the hospital. It was a miracle he was not paralyzed.

One and a third miles south was the Ranch House windmill, the most interesting-looking of the bunch. Its water came up tasting harsh due to the minerals. The well was originally hand dug along the bank of the Agua Poquita Creek in the days when the place was a stagecoach stop. What can best be described as a formidable concrete caisson was fashioned above the original well decades ago. It inched up from the ground, reaching to about eight feet from the base, tapered steeply. It was capped flat with concrete, forming a round platform 30 feet across. It provided a suitable foundation to support four concrete legs encasing pipe that angled inward for another sixteen feet on which a round 800-gallon concrete cistern rested. Higher still, atop all of that, was anchored the topmost quarter of the windmill, bolted to the shallow concrete cone topping the cistern. It was but one example of South Texas rustic beauty hidden in the brush, away from appreciating eyes.

Finally, a little over a mile south of the tall whisky salt cedars of the Ranch House corrals was what we called the South Pasture. Supplying water to the cattle there was its namesake windmill, and owing to its location, the area was not trafficked much, nor was there much sampling of the water there. Ricky recalls it being okay. Of all the windmills, it was planted the most south on the property.

These wells averaged five to seven rods deep, each sucker rod being 21 to 23 feet long. That translated into wells reaching down 110 to 160 feet to the water table. All told, the ranch maintained ten windmills, each distinct, each with a history, and each requiring routine care. That could be entertaining because the order, “We’re gonna pull the windmill,” triggered an uplifting sensation in my younger days. It meant hot summer days in a place that was home and familiar, using my muscles alongside the family males.

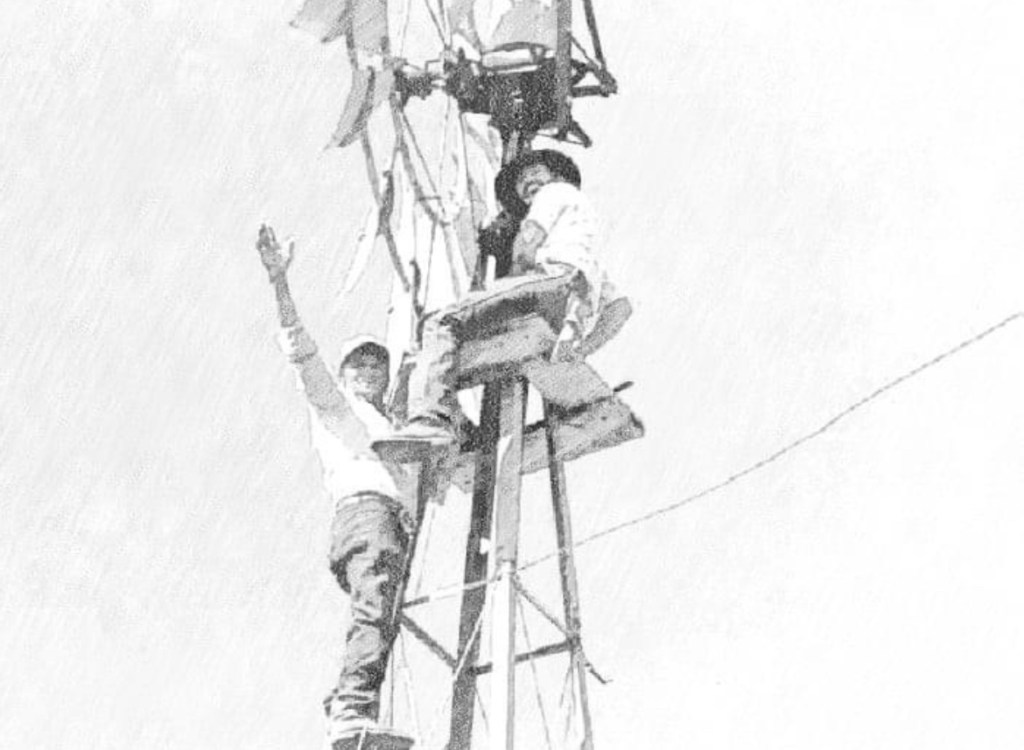

In the 1970s we “pulled” windmills by hand, meaning, we did not have the benefit of an electric winch mounted on a pickup’s bumper to pull up the sucker rods. Rugged man-muscle did the heavy lifting. It was a minimum two-man job… two strong men who were each accustomed to the work and familiar with the tools and equipment it called for. This was no place for a novice.

The first sign of a problem at a windmill was poor water delivery or none at all. That probably meant worn leather cups. With regular use, leathers needed to be replaced every two to five years, and with ten windmills in constant use, pulling a windmill was not uncommon. Neoprene leathers lasted longer and came at a higher cost, but Dad preferred leather. “Trabajan mejor,” he claimed… and perhaps they did perform better. He certainly had more experience than any of us in that department. The best part of those days was working alongside Dad, my younger brothers, and Dick Shimmer with his frisky dogs Rusty and Rex running about. Rusty was a red golden retriever who got bit by a rattler a few years later. He did not survive the encounter. Rex, a long-legged mix breed with an over-active libido, was laid to rest on his last living day at the bottom of the hole dug out for the flagpole at the Alamosa Animal Hospital in Alice, Texas. Dick set old Rex down at the bottom of the hole before the concrete was poured in. Rex went into the dog afterlife minus one eye. Years earlier, Dick had discharged an irritable blast with a 12-gauge in the dog’s direction and blinded one side. Dick always felt bad about that mishap. Rex fathered my favorite all-time companion, Charlie. My dog’s been gone twenty-nine years as of this writing and his love and loyalty are still missed.

Before working on a windmill, an unspoken partnership between you and Mother Nature was established. She handed you a clear and calm day, ideal labor conditions for windmill work. You turned over your blood, sweat, and thanks, grateful you walked away from the job at the end of the day with all your fingers attached. But we were never only two on the job. We were plenty of hands and each knew his work and the tools for the job.

We first set the brake to the windmill at the bottom of the tower. A lever about the length of your arm bolted to one of the angle iron legs was pulled down into the lock position, preventing the fan from turning. A heavy-gauge wire ran up to the lever on the braking mechanism below the gearbox at the top of the windmill. Once that was locked, the pump rod dropping down from the gearbox could be disconnected from the uppermost sucker rod, but not before the stand pipe was unthreaded at ground level near the base of the four legs. With that secured clear of the well pipe, we would pull up the pump rods through the well pipe, disconnecting each by breaking and then turning the couplers that connected the sucker rods together. The pipe would be hit hard with a hammer before trying to loosen them. It was especially important to hold on to the rod immediately below or it could drop to the bottom of the pipe into the cylinder. No one wanted to blindly fish out one of those.

The old sucker rods were fashioned from white ash. That wood produced a straight grain, ideal for rods that averaged 20-feet. If you can still find them, they run six to eight dollars a foot. That is a pricey rod. Fiberglass rods are more commonly used now and are half the cost. The reason for wooden rods was that they floated in the water when pumping, so the windmill did not have to lift as hard, hence the windmill did not work so tough, pumping efficiently even in a slight breeze. The life of a rod depended on the well. Some of the old wells were not drilled straight and if a wooden rod rubbed on the pipe, it would not have a long life.

The rods came up steadily, each stacked upright against a crook in the support angle iron crisscrossing above our heads. Some windmills produced a yellowish mineral sludge that coated the rods. It looked like a watery mustard. The last rod out of the pipe had the plunger screwed on the end. It slid up and down a 24-inch brass cylinder in an eight to ten-inch stroke, depending on the windmill, gradually drawing up water if the cups were good. The plunger fitted three leathers. All would be replaced with new. Dad taught us to knead the cup to soften the leather before setting it in the plunger. This ensured that swelling in the cup happened quicker. Then the whole process was performed in reverse. The windmill had been pulled and returned to good working order. Tools were collected. The work area was given a once over, and a silent thanks drew a smile for a job well done.